By Bobbie Ysabelle Matias

A family goes through their usual day-to-day life as screams and gunshots ring from afar.

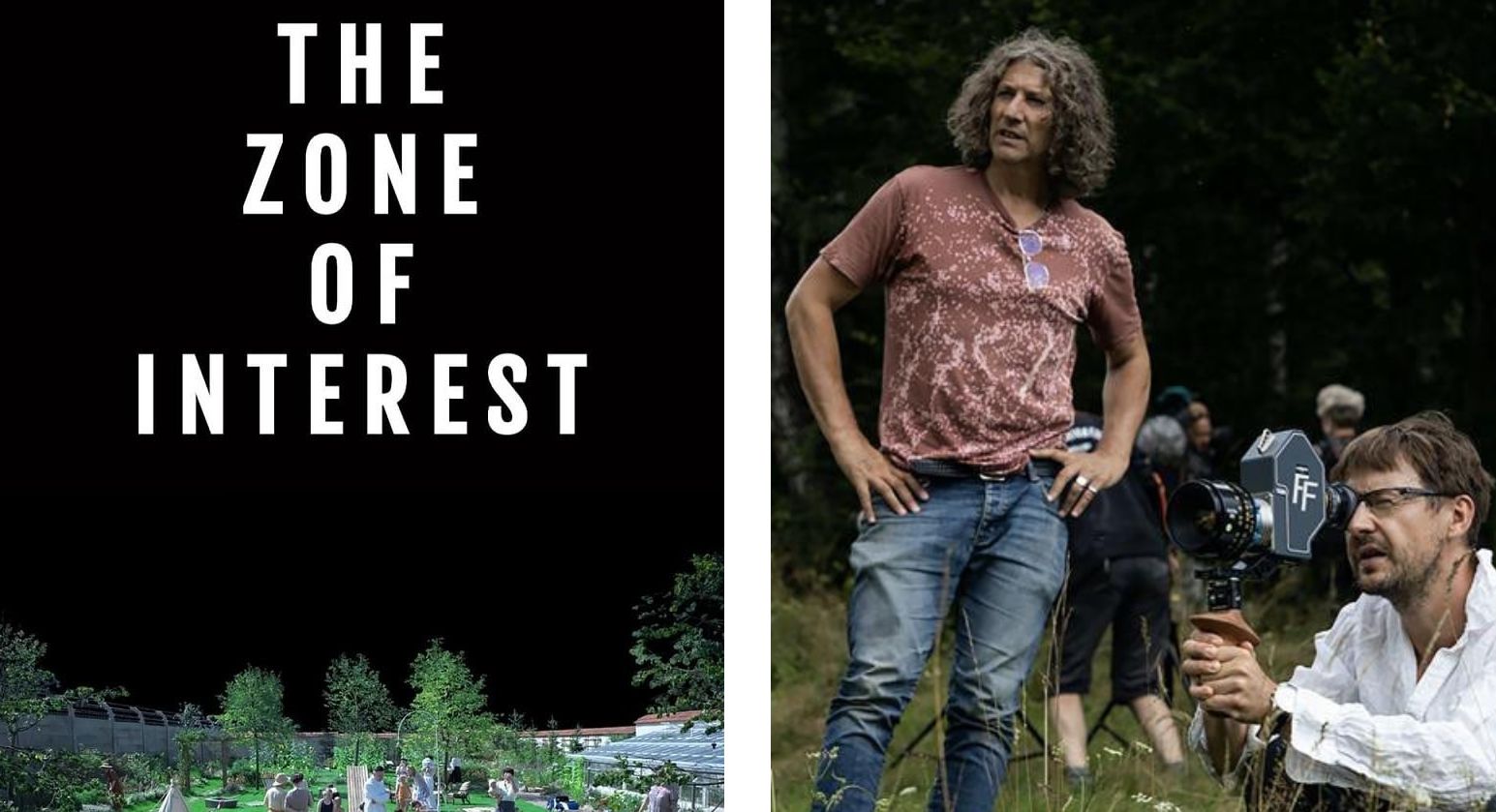

This is the premise of The Zone of Interest, a film set during the Holocaust in WWII Poland about real-life Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Hoss and his wife Hedwig as they build their family’s dream life while living next to a concentration and extermination camp.

Director Jonathan Glazer spent a decade chasing after an unformed idea for a movie, and after reading a preview of Martin Amis’ book ‘The Zone of Interest’, a story told from the viewpoint of a fictional Nazi commandant based on Hoss, Glazer knew he wanted the film’s story to be “not of those within the camp, but those who ran it”.

It was only on his visit to the Hoss’ family home in Poland did he decide that he would tell two different stories in one film – one told through what the audience sees and the other through what they hear.

To achieve this, Glazer recruited Johnnie Burn for the sound design, Tarn Willers, and Mica Levi, who composed the movie’s score, which, although sparingly used, was present in scenes that served to disorient the viewers.

‘Submerging’ the audience

The film begins with minutes of nothing but a black screen and a haunting atonal drone.

Explaining the intro to Rolling Stone magazine, Glazer said he “wanted viewers to realize that they’re submerging”.

“It was a way of tuning your ears (in) before you tune your eyes to what you’re about to view,” he said.

From then on, the audience was treated to the beauty of the countryside and the domesticity of the Hosses in their family home.

The characters went through the banality of their everyday lives, ignorant of the atrocities taking place just over the walls surrounding their “paradise garden”, and sometimes, even joking about it.

‘Ambient genocide’

Listen closely, however, and a horrifying fact will make itself known.

In the first few minutes of the movie, Rudolf’s wife and kids surprised him with a boat for his birthday.

Distinct pops could be heard in the background, drowned out by the family’s celebration and the baby’s cries.

The flowers in Hedwig’s “paradise garden” danced in the air as blood-curdling screams from the prisoners and the guards’ gunshots echoed from the camp.

This juxtaposition was described by a writer as “ambient genocide”, Glazer shared in an interview with ScreenDaily.

“The sound was a huge part, the sound is the other film, and, arguably, the film, for me,” he said.

READ MORE: Seeking truth in warfare: The world calls for fearless journalism

Ambiguity and mental imagery

The film did not once show any of the violence in the story, with the only scene inside the camp being a close-up shot of Rudolf as the prisoners’ cries assaulted the viewer’s senses.

And this was Glazer’s plan from the beginning, Burn told the BBC, as the director did not want to “show the images that people have already seen”.

“(With the sound) we’re deliberately ambiguous. Is that a scream or is it a train whistle? Or is it the baby in the house?” Burn said.

“Depending on what mood you’re in, you might hear it differently on different occasions. Your mind goes off and starts making its own visions, so we’re drawing pictures in people’s heads based on a collective mental imagery and knowledge that people already have.”

Burn, who also worked on the sound design for ‘Nope’ and ‘Poor Things,’ made sure to be as accurate as possible when coming up with the movies’ sound library.

He went as far as reading through witness testimonies from Auschwitz survivors, which contained “direct references to sound” and “lots of vivid descriptions of murder and torture”.

He also avoided employing actors to re-enact the sounds he needed, instead opting for extensive field recordings, such as attending a protest in France with hidden mics on.

These efforts did not go unnoticed by critics, with his and Willers’ work winning the Oscar for Best Sound last year.

Overlooking violence and desensitisation

The Zone of Interest portrayed the horrors of the Holocaust in a way that provides a fresh but still haunting perspective relevant to today’s fragile geopolitical situation.

Moreover, the differing stories told by the film’s sound and visuals boil down to what it hopes to tell its audience – that humans are more than willing to overlook violence to remain in their bubble of comfort and privilege.

Burn also shared how he was desensitized to the sounds while working on the film, which he said is a common reaction.

“I experienced that too – it’s exactly for that reason the sounds in the film actually get marginally louder as the film goes on because we dial (them) out. It’s really weird, as a human you end up thinking, ‘it’s just another scream, I can dial that out, fine’,” said Burn.

“That’s what Jonathan’s trying to say, we’re all on that slippery slope (to desensitization). The film is about what humans do to other humans, so let’s try and get rid of this violence.”

READ NEXT: US health, animal experts scramble to contain the spread of bird flu